Brugada Syndrome: Diagnosis and Risk Stratification

Brugada Syndrome: Diagnosis and Risk Stratification

Hello friends, this is the modified version of my talk at Indian Heart Rhythm Society Conference, New Delhi, 2023, on Brugada Syndrome. Hope you will enjoy this session.

Initial description of Brugada syndrome in 1992 was that of syncopal episodes and/or sudden death in persons with structurally normal heart and a characteristic ECG pattern of right bundle branch block with ST segment elevation in leads V1 to V3. Sometimes individuals with a diagnostic ECG may be totally asymptomatic and may be having a family history of sudden death. Genetic nature of the disorder and mutation in sodium channel gene was described in 1998. Even though mutations in other channels have been described in Brugada syndrome, only those in SCN5A gene are considered to be definitely disease causing. Yet, SCN5A variants are identified in only about one fifth of persons with Brugada syndrome. Brugada syndrome is thought to account for about one fourth of sudden cardiac deaths in individuals with structurally normal heart.

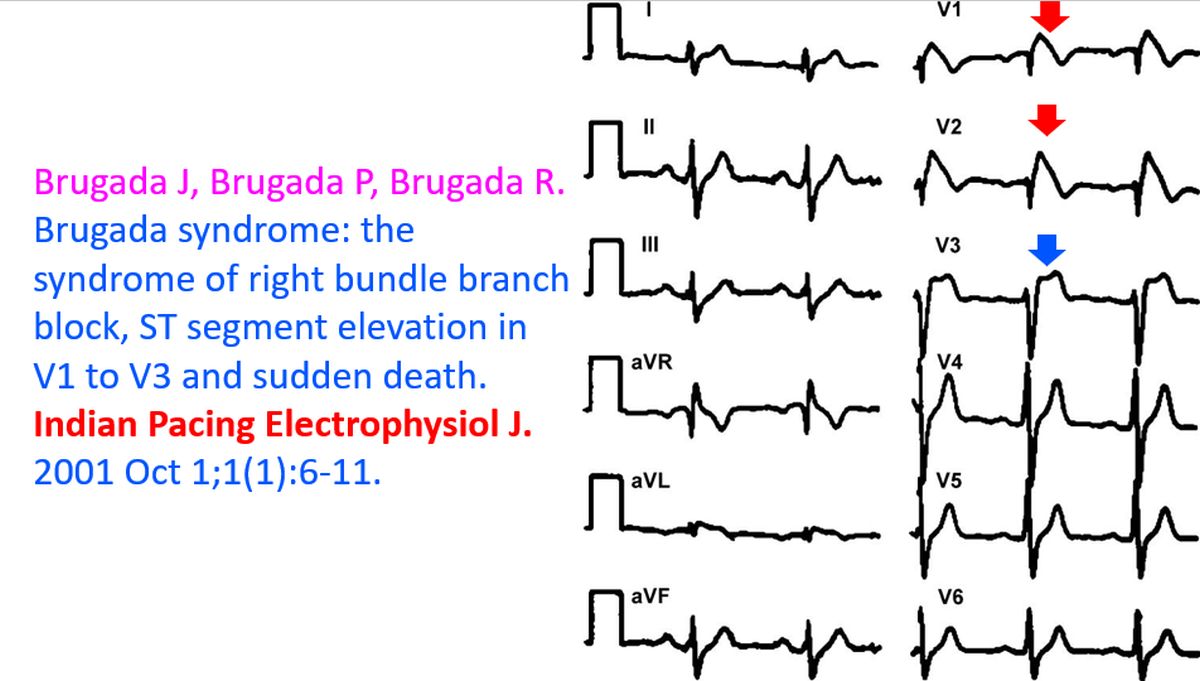

I am always happy to see this ECG of Brugada syndrome as it was sent to me by Prof. Josep Brugada way back in 2001 for the inaugural issue of IPEJ, along with his review article. Prof. Brugada’s article was the first ever article which I received for IPEJ and it gave a great boost to the debut issue of the journal [1]. ECG pattern seen in V1 and V2 with coved ST segment elevation has been called as the type 1 pattern, while the saddle shaped ST elevation 1 mm or more, seen in V3 has been called type 2 pattern.

Brugada syndrome manifests mostly in adulthood and has a definite male preponderance of almost eight fold. Autosomal dominant inheritance pattern has been noted. Type 1 pattern occurs in about 1 in 2000 individuals while type 2/3 can occur in about 1 in 500. It is most common in Asia, followed by Europe and United States. It can be as low as 1 in 20,000 in children. Male preponderance is only apparent after adolescence.

In Brugada syndrome dysfunctional voltage gated sodium channels NaV1.5 have delayed activation and earlier inactivation. This leads to shortening of action potential duration. There is additional shortening of action potential duration at higher temperatures. This is the proposed mechanism of precipitation of arrhythmias in Brugada syndrome during febrile episodes. That is why prompt treatment of fever is an important preventive strategy to be deployed in those with Brugada syndrome [2]. Alcohol and several medications have been considered to be triggers in Brugada syndrome.

Only one third of cases are symptomatic while two third have only the ECG pattern at diagnosis. One third of these are detected on family screening of persons diagnosed with Brugada syndrome.

Sodium channel blockers are used to unmask the Brugada pattern in ECG in clinically suspected cases. Ajmaline is the most powerful of these, but could have some decrease in specificity. Other drugs are flecainide, procainamide, and pilsicainide is used in Japan. There is a potential risk for drug challenge in that life threatening ventricular arrhythmias could be precipitated. Hence drug challenge is to be done only in a monitored intensive care facility. With proper precautions, risk can be reduced. It is seldom done in pediatric age group.

Drug challenge has to be terminated if ventricular arrhythmias, type 1 ECG or QRS widening more than 130% of baseline are noted. The issue of stopping drug challenge is mainly while giving intravenous medication. In some situations drug challenge may be done with oral medications, under close monitoring.

Usual ECG starts with V1 in fourth intercostal space. Taking one or two intercostal spaces higher may improve the sensitivity of detecting Brugada pattern by 1.5 times. This is mainly to account for the individual variation in anatomical location of right ventricular outflow tract, the main location of electrophysiological abnormalities in Brugada syndrome.

These are the conditions which have to be considered or excluded as they can sometimes manifest Brugada pattern on ECG. They include myocardial ischemia, acute pericarditis, pulmonary embolism, external compression due to mass over the right ventricular outflow tract region, and metabolic disorders like hyper or hypokalemia and hypercalcemia.

These are the conditions which have to be considered or excluded as they can sometimes manifest Brugada pattern on ECG. They include myocardial ischemia, acute pericarditis, pulmonary embolism, external compression due to mass over the right ventricular outflow tract region, and metabolic disorders like hyper or hypokalemia and hypercalcemia.

According to a recent systematic review and meta-analysis, spontaneous type 1 ECG had 2.4% annual incidence of serious arrhythmic events, while one induced by sodium channel blockers have a lower risk at 0.65% annually [3].

It has been thought that females and those older than 60 years have a higher risk, though the age factor is not well proven.

Other factors which are not well confirmed are inducible ventricular fibrillation on electrophysiology study, sinus node dysfunction in females, S wave in Lead 1 > 0.1 mV in amplitude and/or > 40 ms in duration, fragmented QRS and type 1 Brugada pattern in inferior or lateral leads. If three or more extra stimuli are needed for induction of ventricular fibrillation, the importance comes down further. Opinion is divided on the need for electrophysiology study.

Other parameters which are thought to convey risk in Brugada syndrome are Tpeak-Tend >100 ms in chest leads, early repolarization pattern in inferior leads, post exercise ST segment elevation and diurnal burden of Type 1 ECG pattern on Holter monitoring [4].

Still more are factors are age < 18 years, sudden cardiac death in first degree relative, SCN5A mutations, atrial fibrillation, PR interval > 200 ms, QRS duration > 120 ms, presence of late potentials and aVR sign, manifested as R wave ≥ 0.3 mV or R/q ≥ 0.75.

Shanghai Score was arrived at in a consensus conference held in 2016. Spontaneous type 1 ECG has the highest number of points at 3.5, while fever-induced type 1 ECG has 3 points. Type 2/3 ECG which gets converted to type 1 pattern with sodium channel blockers have 2 points.

In clinical history, unexplained cardiac arrest or documented ventricular fibrillation and polymorphic ventricular tachycardia gets 3 points, nocturnal agonal respirations 2 points, suspected arrhythmic syncope 2 points, syncope of unclear etiology one point and atrial fibrillation or flutter at age below 30 years without a clear etiology gets half a point.

In family history, first or second degree relative with definite Brugada syndrome gets 2 points, suspicious sudden cardiac death with fever, at night or with Brugada-aggravating drugs in first or second degree relative gets one point while unexplained sudden cardiac death before 45 years of age in first or second degree relative with negative autopsy findings gives half a point.

Genetic testing is not considered as diagnostic of Brugada syndrome. Penetrance is only 50% in families with Brugada syndrome, while those without a pathogenic variant may have clinical Brugada syndrome.

If 3.5 or more points were there it was considered probable or definite, possible if there were 2-3 points and nondiagnostic if the score was below 2 points [5].

Atrial arrhythmias may occur in about 10% of those with Brugada syndrome and atrial fibrillation is the commonest sustained atrial arrhythmia. Sometimes, treatment of AF with class Ic drugs may unmask underlying Brugada syndrome. Incidentally, our review on AF in Brugada syndrome was published in JACC some time back [6].

References

- Brugada J, Brugada P, Brugada R. Brugada syndrome: the syndrome of right bundle branch block, ST segment elevation in V1 to V3 and sudden death. Indian Pacing Electrophysiol J. 2001 Oct 1;1(1):6-11.

- Krahn AD, Behr ER, Hamilton R, Probst V, Laksman Z, Han HC. Brugada Syndrome. JACC Clin Electrophysiol. 2022 Mar;8(3):386-405.

- Rattanawong P, Kewcharoen J, Kanitsoraphan C, Vutthikraivit W, Putthapiban P, Prasitlumkum N, Mekraksakit P, Mekritthikrai R, Chung EH. The utility of drug challenge testing in Brugada syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2020 Sep;31(9):2474-2483.

- Gourraud JB, Barc J, Thollet A, Le Marec H, Probst V. Brugada syndrome: Diagnosis, risk stratification and management. Arch Cardiovasc Dis. 2017 Mar;110(3):188-195.

- Antzelevitch C, Yan GX, Ackerman MJ, Borggrefe M, Corrado D, Guo J, Gussak I, Hasdemir C, Horie M, Huikuri H, Ma C, Morita H, Nam GB, Sacher F, Shimizu W, Viskin S, Wilde AA. J-Wave syndromes expert consensus conference report: Emerging concepts and gaps in knowledge. Heart Rhythm. 2016 Oct;13(10):e295-324.

- Francis J, Antzelevitch C. Atrial fibrillation and Brugada syndrome. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008 Mar 25;51(12):1149-53.