Carcinoid heart disease

Carcinoid heart disease

Carcinoid heart disease occurs in rare neuroendocrine tumors producing carcinoid syndrome. Carcinoid tumours are most often located in the gastrointestinal system, though they can also occur in the bronchopulmonary system [1].

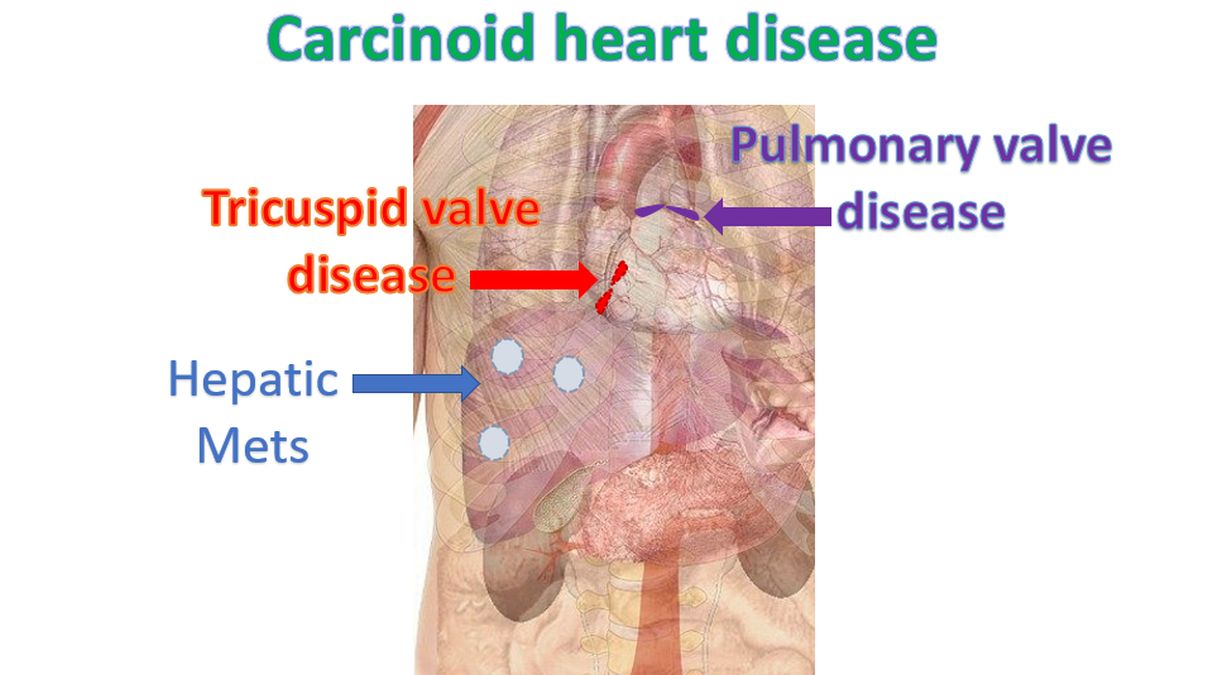

Usual dictum is that right sided heart valves are involved when the tumour has metastasized to the liver as liver acts as the first filter for the products secreted by the tumour, mainly serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine, 5-HT). Other products of neuroendocrine tumours include tachykinins, kallikrein and prostaglandins. Severe involvement of right sided heart valves can lead to heart failure. Left sided heart valves can be involved when there is tumour in the lungs as lungs are the second filter for the products of carcinoid tumour.

Carcinoid syndrome manifests with flushing of skin, diarrhea and palpitation. Asthma like symptoms with wheezing and breathlessness can also occur. Watery diarrhea with abdominal cramps are the hallmarks of carcinoid syndrome. Purplish skin lesions may be noted on the face, especially on the nose and upper lip.

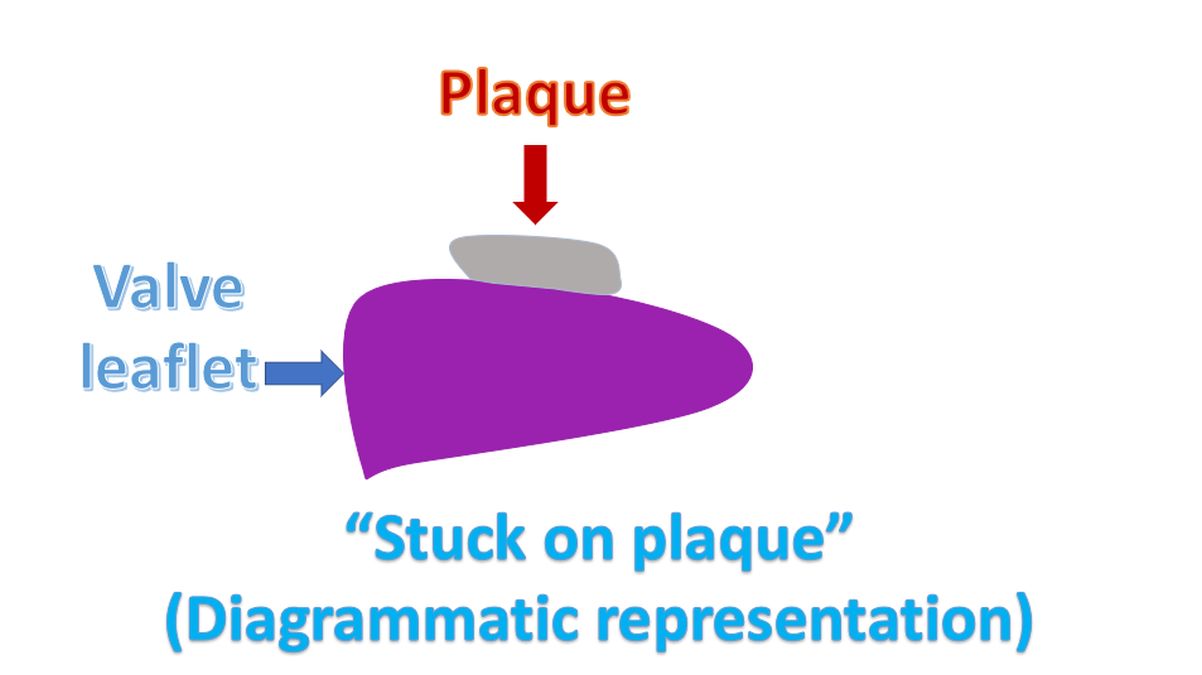

“Stuck on plaque” is the description given to the lesions on the valves in carcinoid heart disease and anorexigen associated valvular heart disease. The lesions appear “stuck on” the leaflets without inflammation or damage to the underlying valve structure [2,3].

A surgical pathology study of carcinoid heart disease from Mayo Clinic had data on 139 valves from 75 patients, collected over 20 years [4]. Of the 139 surgically excised valves, 73 were tricuspid, 55 pulmonary, 6 mitral and 5 aortic. This gives the pattern of valvular involvement in carcinoid heart disease. Pure regurgitation was the most common finding, noted in 80% of the tricuspid valves, 97% of mitral valves and 96% of aortic valves. On the other hand, pulmonary valve was often stenotic and regurgitant as was noted in 52% of the pulmonary valves. Pure pulmonary regurgitation was noted in 30% of the pulmonary valves. Valve dysfunction was due to carcinoid plaques which caused thickening and retraction. Thickening was due to both cellular proliferation and deposition of extracellular matrix. The right sided predominance of carcinoid heart disease was documented by the fact that 92% of the excised valves were tricuspid and pulmonary.

The cardiac involvement in carcinoid may sometimes be clinically silent. Progressive right heart failure with anasarca and cardiac cachexia can occur later on. Elevated jugular venous pressure and murmurs of tricuspid and pulmonary regurgitation may be audible. Peripheral edema, ascites and pulsatile hepatomegaly may also be noted in advanced cases [1].

Elevated urinary 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid (5-HIAA) has been correlated with increased risk of progression of carcinoid heart disease. Chromogranin A is a sensitive marker for carcinoid. N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) is also a useful indicator of cardiac failure in carcinoid heart disease. Echocardiography documents the valvular thickening and retraction as well as the degree of regurgitation and stenosis. The leaflets may be fixed in half open position producing regurgitation and stenosis.

Positron emission tomography using synthetic radiolabeled octreotide with 68Ga will localize the tumour. Other than the treatment of heart failure which is along the usual lines, somatostatin analogues are also useful for carcinoid syndrome. Tumour debulking may be considered with hepatic artery embolization and palliative hepatic cytoreductive surgery. An important perioperative management is continuous somatostatin analogue (octreotide) infusion which should be started at least 2 hours before surgery and continued for 48 hours afterwards, followed by slow tapering. The role of somatostatin analogues in diagnostic imaging and treatment is because the tumor cells express specific somatostatin receptors on their surface membrane [1].

References

- Grozinsky-Glasberg S, Grossman AB, Gross DJ. Carcinoid Heart Disease: From Pathophysiology to Treatment–‘Something in the Way It Moves’. Neuroendocrinology. 2015;101(4):263-73. doi: 10.1159/000381930. Epub 2015 Apr 9. PMID: 25871411.

- Proesmans S, Van Fraeyenhove F, Dossche K, Mattelaer C, Scott B. Carcinoid heart disease: a remarkable recovery. Acta Clin Belg. 2015 Dec;70(6):453-6.

- C J Knott-Craig, H V Schaff, C J Mullany, L K Kvols, C G Moertel, W D Edwards, G K Danielson. Carcinoid disease of the heart. Surgical management of ten patients. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1992 Aug;104(2):475-81.

- Simula DV, Edwards WD, Tazelaar HD, Connolly HM, Schaff HV. Surgical pathology of carcinoid heart disease: a study of 139 valves from 75 patients spanning 20 years. Mayo Clin Proc. 2002 Feb;77(2):139-47. doi: 10.4065/77.2.139. PMID: 11838647.