Diagnosis of ventricular tachycardia

Diagnosis of ventricular tachycardia

The usual dictum is that a wide QRS tachycardia is ventricular tachycardia unless proved otherwise. Other causes of wide QRS tachycardia are supraventricular tachycardia with aberrant conduction and supraventricular tachycardia with pre-existing bundle branch block or pre-excitation. Differentiating these in a patient presenting to the emergency room with hemodynamic compromise is often not an easy task, though there are several published criteria for this. Often these patients are immediately cardioverted to avoid a catastrophe, which is the rightful decision in that situation. Discussion on whether it was ventricular tachycardia or supraventricular tachycardia then starts as a retrospective exercise. Differentiation has importance in further management, though sometimes an electrophysiology study is needed for us to be sure.

Ventricular tachycardia can be broadly divided into monomorphic (MMVT) and polymorphic (PMVT), based on the beat to beat consistency of QRS complexes. Another division is into sustained and non-sustained, based on duration. A ventricular tachycardia which lasts more than 30 seconds or needs termination prior to that due to hemodynamic compromise is defined as sustained ventricular tachycardia. Non-sustained ventricular tachycardia (NSVT) lasts less than 30 seconds. A special type of ventricular tachycardia is a bidirectional ventricular tachycardia with opposite polarity for alternate QRS complexes. Bidirectional VT is seen in digoxin toxicity, catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia (CPVT) and Andersen-Tawil syndrome (LQT7).

As mentioned by late Prof. Dr. HJJ Wellens, a reasonable hemodynamic status during a tachycardia may erroneously lead to the diagnosis of supraventricular tachycardia. Administering calcium channel antagonists in this situation can be dangerous [1]. Analyzing the ECG in depth may be useful not only to differentiate between ventricular and supraventricular origin, but also may give a hint to the etiology and site of origin within the ventricle.

There are several supraventricular tachycardias which can present with wide QRS complexes. They include ectopic atrial tachycardia, atrial flutter, atrial fibrillation, atrioventricular nodal re-entrant tachycardia and atrioventricular re-entrant tachycardia. In atrioventricular re-entrant tachycardia, antidromic variety has wide QRS complex consistently while the in case of other tachycardias, another mechanism is needed to produce a wide QRS. This could be rate dependent phase 3 aberrancy in which the refractory period of one of the bundles is reached with a fast rate. A pre-existing bundle branch block is another possibility. Conduction over a bystander accessory pathway is another possibility.

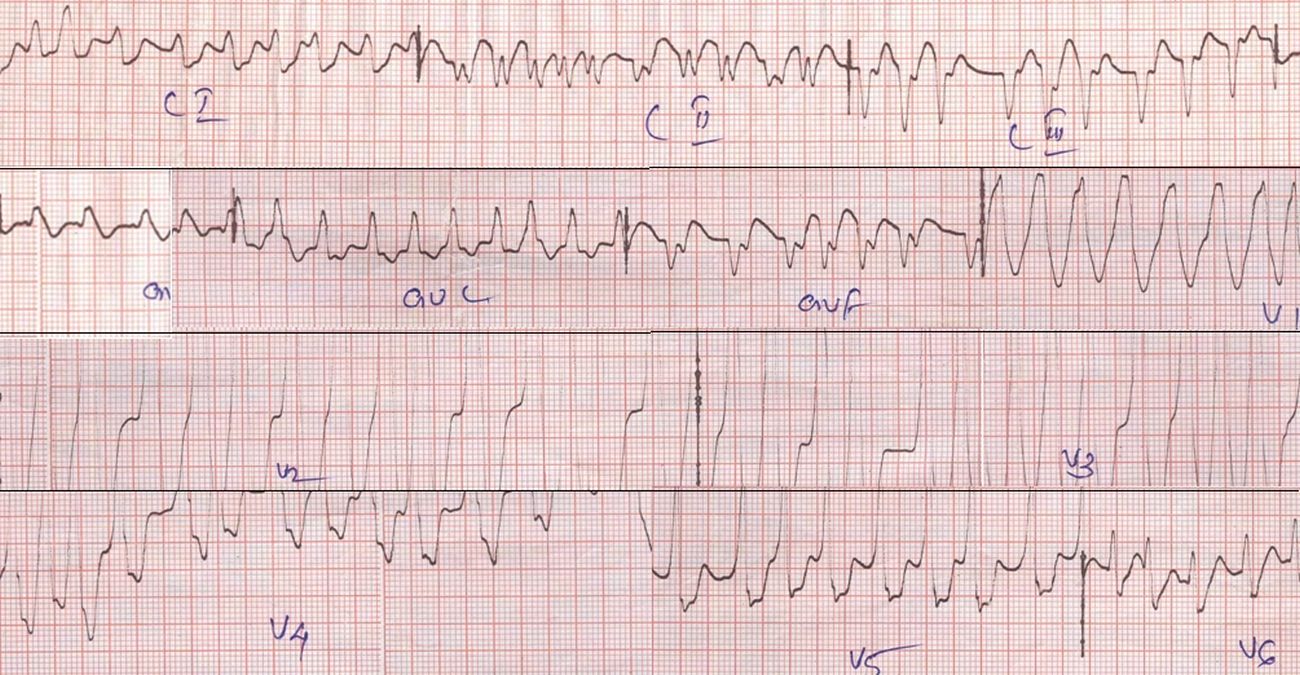

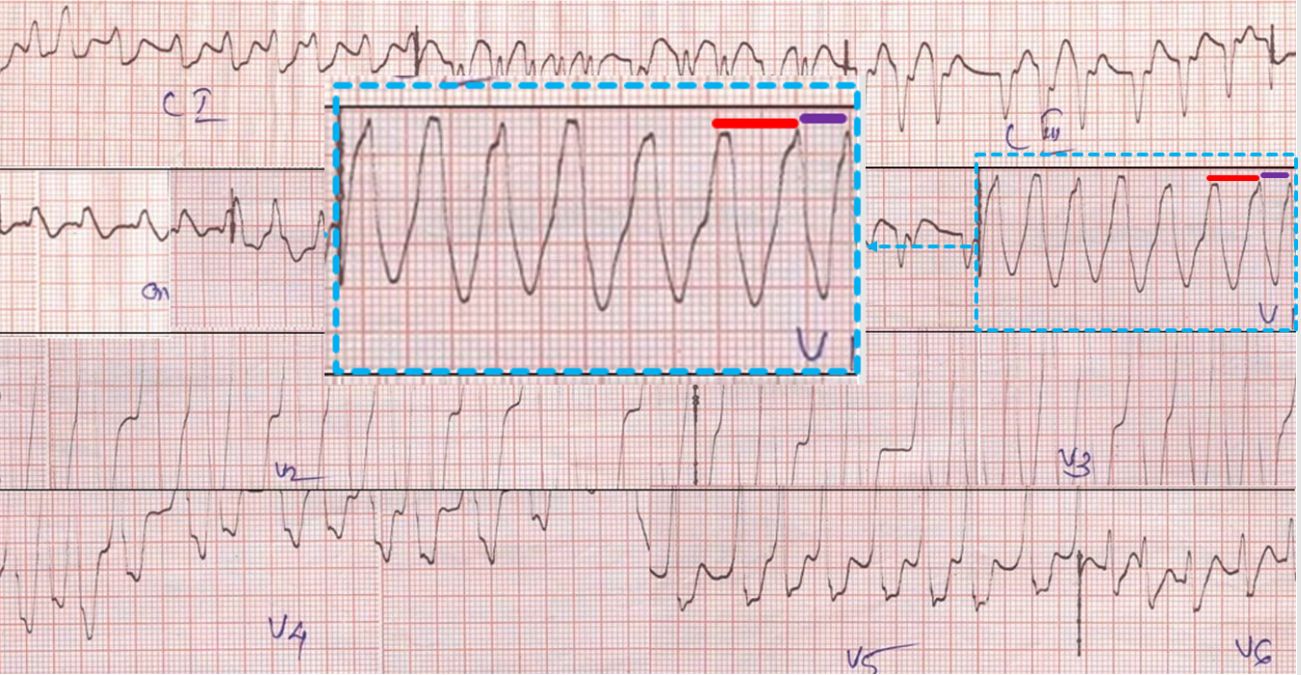

Of the tachycardias, atrial fibrillation is irregular while others are regular. But in case of atrial fibrillation and wide QRS tachycardia due to an accessory pathway, it may be often thought to be regular due to the fast rate. In atrial fibrillation with accessory pathway, fast ventricular rates are seen for two reasons: (1) Conduction over both AV nodal pathway and accessory pathway (2) The refractory period of accessory pathway decreases as the rate increases, allowing rapid transmission of impulses to the ventricles. This is a potential risk as very fast ventricular rates can degenerate into ventricular fibrillation. That is why AF with WPW syndrome and fast ventricular rate needs prompt cardioversion.

Close scrutiny of the tracing in AF with WPW syndrome and fast ventricular rate will show the variation in RR interval, usually more than 50% between the shortest RR interval and the longest RR interval. But at one look, it can very well be mistaken for a regular wide QRS tachycardia in an emergency situation. See lead V1 in the strip above, for example. V1 is a common monitoring lead and it is easy to interpret the monitor rhythm as ventricular tachycardia as soon as the leads are connected. Still there is about 50% difference between the RR intervals of the last two beats in the small strip of V1.

Looking for dissociated P waves is an important way of confirming ventricular tachycardia in a broad QRS tachycardia. Anyone who has tried it would have found it difficult to identify the P waves in a fast rhythm especially if the baseline is not very steady. Artefacts are quite common in a patient with hemodynamic compromise as they can be restless. P waves can be identified in relatively slower VT fairly easily, if the baseline is steady. Other evidence of atrioventricular dissociation like cannon waves in jugular venous pulse, variation in intensity of first heart sound and variation in systolic blood pressure are useful in some cases [2]. Practically this would mean a varying pulse volume in a regular rhythm due to variation in atrial help for ventricular filling as the P-QRS relationship varies from beat to beat. Some would say that pulse will feel like atrial fibrillation while heart sounds would be regular.

Though dissociated P waves are the norm in ventricular tachycardia, occasionally regular P waves can occur due to regular retrograde (VA) conduction in ventricular tachycardia. Regular retrograde P waves will cause regular cannon waves in the jugular venous pulse. But a junctional tachycardia can also cause regular cannon waves. Though atrial and ventricular contractions are nearly simultaneous in atrioventricular nodal re-entrant tachycardia also, cannon waves are difficult to appreciate due to the fast rate. Some have called the regular cannon waves as ‘frog positive’ due to the resemblance to the appearance of a croaking frog! In short, though regular cannon waves are more likely in supraventricular tachycardia, it can also occur in ventricular tachycardia with regular retrograde conduction.

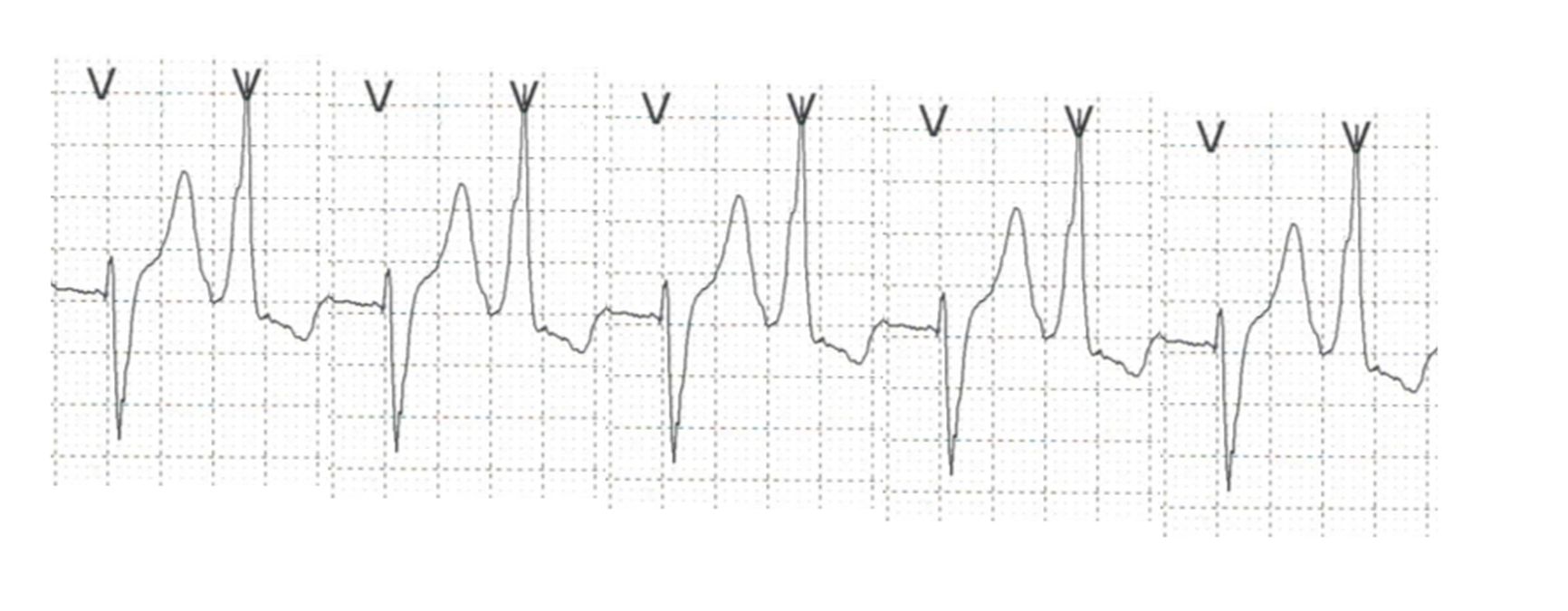

Another feature useful for differentiating VT from SVT is the presence of capture beats and fusions beats, again noted in a relatively slow VT. Capture beat is an appropriately timed sinus beat with preceding P wave and narrow QRS complex interrupting a ventricular tachycardia. If the sinus beat fuses with a simultaneous ventricular tachycardia beat, it is called a fusion beat. Fusion beat is also known as Dressler beat and has a morphology and width intermediate between the sinus beat and VT beat. In the initial description by William Dressler et al, this was noted when the VT rate was less than 150/min [3]. Dressler beats have been described in ventricular tachycardia occurring during atrial fibrillation as well [4].

A ventricular premature complex occurring during the ventricular tachycardia, arising in the same ventricle as that of the tachycardia origin can also cause sudden narrowing of a QRS complex during VT. Retrograde conduction of VT can produce a ventricular echo beat which fuses with a tachycardia beat and cause sudden narrowing of a QRS complex during a VT [1]. So, there are multiple mechanisms for production of fusion beats in ventricular tachycardia.

A rare cause of a wide QRS supraventricular tachycardia with AV dissociation is junctional ectopic tachycardia (JET) with bundle branch block. This typically occurs in a post cardiac surgery situation. Though JET is a difficult to treat arrhythmia, it responds to induction of hypothermia. A congenital variety of JET occurs in infancy but is usually a narrow QRS tachycardia [5].

There are several morphology criteria for differentiating VT from SVT with aberrancy, with varying sensitivities and specificities. A VT originating from the lateral wall is likely to have a wider QRS than one originating from the interventricular septum. But the presence of scar tissue after a myocardial infarction, ventricular hypertrophy, and muscular disarray as in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy can also widen the QRS. Conduction of supraventricular tachycardia over an accessory pathway can also produce a wider QRS.

QRS axis during VT helps in identifying the origin. Superior axis suggests origin from the apex while an inferior axis suggests origin from the basal ventricle. A superior axis in an RBBB pattern would suggest VT. Inferior axis in an LBBB pattern tachycardia is seen in right ventricular outflow tract tachycardia (RVOT VT).

A negative concordance is present when all precordial leads show a negative QRS complex and is suggestive of VT originating from the apical area. Positive concordance can occur in VT originating from the left posterior wall or during tachycardias using a left posterior accessory atrioventricular pathway for conduction. Interestingly, a tachycardia QRS narrower than the sinus rhythm QRS is suggestive of VT. This occurs when a tachycardia originates close to the interventricular septum leading to more simultaneous activation of the ventricles than in sinus rhythm. Of course, this is due to deranged conduction of sinus beats in those with a proximal LBBB.

If an ECG during sinus rhythm is available, it is also useful to document pre-existent bundle branch block, ventricular pre-excitation, and old myocardial infarction. This will help in interpretation as the corresponding tachycardia. Presence of AV conduction disturbances during sinus rhythm would make AV node mediated tachycardias improbable.

References

- Wellens HJ. Electrophysiology: Ventricular tachycardia: diagnosis of broad QRS complex tachycardia. Heart. 2001 Nov;86(5):579-85. doi: 10.1136/heart.86.5.579. PMID: 11602560; PMCID: PMC1729977.

- Harvey WP, Ronan JA Jr. Bedside diagnosis of arrhythmias. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 1966 Mar;8(5):419-45. doi: 10.1016/s0033-0620(66)80030-0. PMID: 5906985.

- William Dressler, Hugo Roesler. The occurrence in paroxysmal ventricular tachycardia of ventricular complexes transitional in shape to sinoauricular beats; a diagnostic aid. Am Heart J. 1952 Oct;44(4):485-93.

- Young RL, Mower MM, Ramapuram GM, Tabatznik B. Atrial fibrillation with ventricular tachycardia showing “Dressler” beats. Chest. 1973 Jan;63(1):96-7.

- Srinivasan C, Balaji S. Neonatal supraventricular tachycardia. Indian Pacing Electrophysiol J. 2019 Nov-Dec;19(6):222-231. doi: 10.1016/j.ipej.2019.09.004. Epub 2019 Sep 18. PMID: 31541680; PMCID: PMC6904811.