Rheumatic aortic regurgitation

Rheumatic aortic regurgitation

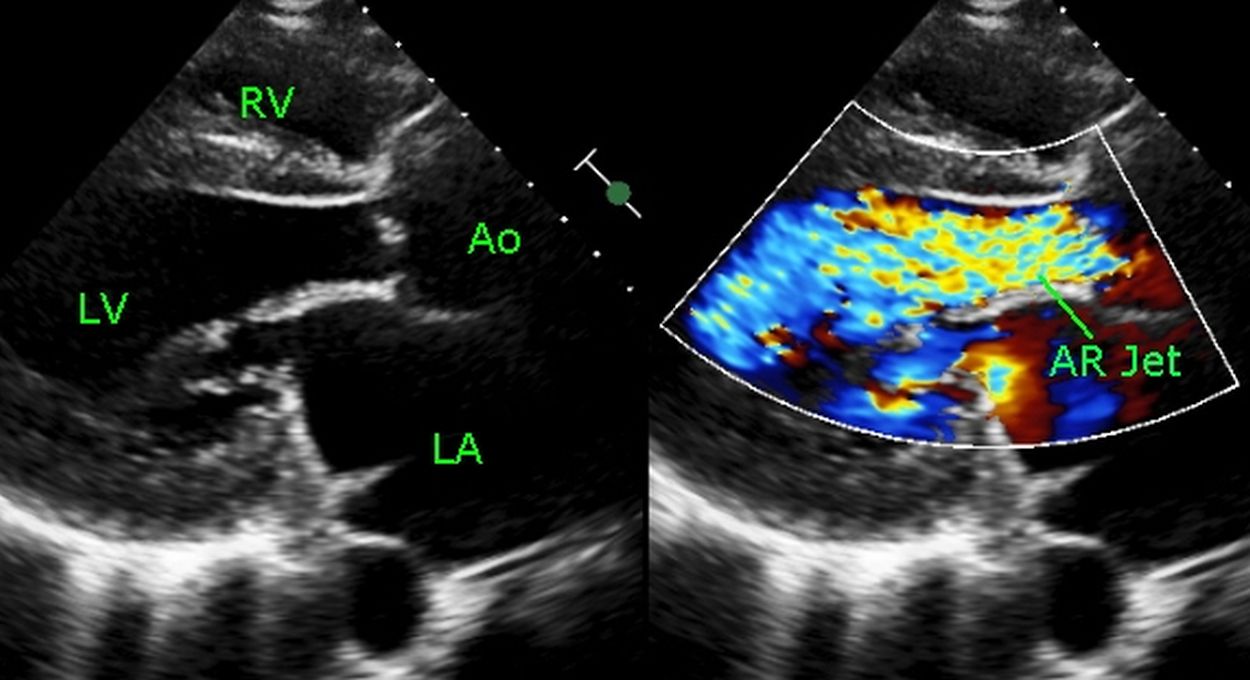

Rheumatic aortic regurgitation can occur in the acute phase of rheumatic fever and disappear later. In the chronic stage, it may progress in severity. Peripheral signs of aortic regurgitation are noted in chronic severe aortic regurgitation due to the rapid aortic run off along with peripheral vasodilatation. Peripheral resistance is reduced in an attempt to reduce the regurgitation and encourage forward flow. High volume collapsing pulse is characteristic of severe aortic regurgitation. Echocardiogram in severe aortic regurgitation is shown below.

Echocardiogram from the parasternal region showing the high velocity mosaic colored aortic regurgitation jet from aortic valve to the left ventricle (AR Jet). RV: Right ventricle, Ao: Aorta, LV: Left ventricle, LA: Left atrium. Both left atrium and left ventricle are dilated in severe aortic regurgitation.

Initially the left ventricle dilates and tries to accommodate the regurgitant volume. In addition to dilatation, there is hypertrophy of the left ventricular wall. This is known as eccentric left ventricular hypertrophy. As time passes, this compensatory mechanism fails and the left ventricle starts failing. Left ventricular muscle can develop fibrotic changes which indicate irreversible late stage disease.

Clinical findings in aortic regurgitation (AR) include high volume collapsing pulse, cardiomegaly with a forceful apex and a high pitched, blowing, early diastolic murmur heard in the aortic area and along the left sternal border. A mid diastolic or presystolic murmur in the mitral area due flow across a functional narrowing of mitral valve in aortic regurgitation is known as Austin Flint murmur.

Peripheral signs of AR are mostly due to the high stroke volume and high pulse pressure. They are noted in severe AR (free AR). These are features of aortic runoff and can occur in other situations of aortic runoff like a ruptured sinus of Valsalva into right atrium.

- Arterial pulsations in the retina: Normally there are only venous pulsations visible on the ocular fundus. In aortic regurgitation, retinal arterial pulsations are visible. This is known as Becker’s sign.

- Hill’s sign: Significant difference between the upper limb and lower limb pressure indicates significant aortic regurgitation. A difference of 20-40 mm Hg is taken as mild, 40-60 mm Hg as moderate and above 60 mm Hg as severe. This is one of the most sensitive signs of aortic regurgitation.

- Muller’s sign: Systolic pulsations of the uvula in aortic regurgitation.

- Dancing carotids: Prominent carotid pulsations due to the wide pulse pressure in aortic regurgitation (Corrigan’s sign).

- de- Musset’s sign: Head nodding sign in aortic regurgitation.

- Bisferiens pulse is more suggestive of free aortic regurgitation than a combination of aortic stenosis and regurgitation. Bisferiens pulse has two peaks in each systole.

- Locomotor brachii is a prominent pulsation of brachial artery seen in aortic regurgitation. It can also be seen in elderly individuals without aortic regurgitation.

- Collapsing pulse or water hammer pulse is noted in the radial artery, with upper limb lifted up passively and felt by the palm of the hand. Water hammer was a toy in the Victorian era in which fall of water in vacuum tube produces a characteristic feel.

- Quincke’s sign: Prominent nail bed capillary pulsations.

- Duroziez murmur/sign: A stethoscope kept over the femoral artery picks up a systolic murmur with proximal compression and diastolic murmur with distal compression. The diastolic murmur is specific.

- Pistol shots sounds can be heard over the femoral arteries and sometimes over the brachial arteries (Traube’s sign).

- Gerhardt’s sign: Hepatic pulsations in severe aortic regurgitation.

- Rosenbach’s sign: Splenic pulsations in severe aortic regurgitation.

- Mayne’s sign: Exaggerated decrease in diastolic blood pressure (more than 15 mm Hg) on raising the upper limb. But the validity has been questioned as this can be noted in younger age without aortic regurgitation.

- Lincoln sign: Prominent popliteal artery pulsations.

- Sherman sign: Prominent dorsalis pedis artery pulsations.

Natural history of rheumatic aortic regurgitation

As the prevalence of rheumatic heart disease is declining, we have to go back to previous studies for the natural history of rheumatic heart disease. One such study from 1971 reported data on 174 young patients with aortic regurgitation followed prospectively for a median period of 10 years [1]. 31 patients developed the triad of moderate or marked left ventricular enlargement, two or 3 ECG abnormalities and abnormal blood pressure. One third of these patients either died or had heart failure or angina within 1 year. 48% had these end points in 2 years while 65% had it in 3 years and 87% in 6 years of having the triad of findings. 71 patients with none of these features had uneventful courses. Among the patients with one or two of the features among the triad, only seven either died (three) or became symptomatic.

Another study published in 1976 reviewed 180 patients with severe aortic regurgitation [2]. 110 of these patients underwent aortic valve replacement. Among the 39 clinical and hemodynamic parameters studied, only heart failure, radiographic heart size, left ventricular hypertrophy and ventricular premature beats were associated with death before surgery. Preoperative factors associated with an unfavorable result after surgery were advanced heart failure, cardiomyopathy, extreme cardiomegaly and ventricular premature beats.

References

- Spagnuolo M, Kloth H, Taranta A, Doyle E, Pasternack B. Natural history of rheumatic aortic regurgitation. Criteria predictive of death, congestive heart failure, and angina in young patients. Circulation. 1971 Sep;44(3):368-80.

- Smith HJ, Neutze JM, Roche AH, Agnew TM, Barratt-Boyes BG. The natural history of rheumatic aortic regurgitation and the indications for surgery. Br Heart J. 1976 Feb;38(2):147-54.